By Katie Koncan, Senior Development Officer

November 2nd was a day I had been looking forward to for the past 7 weeks. On that remarkably crisp and sunny November morning, I was lucky enough to be allowed to attend a private dialogue event of individuals, researchers, allies and activists, leaders, and policy whizzes who were all experts in their own ways on one topic: conversion therapy. I do want to acknowledge that I was allowed to be there. This was a private event on a topic that is highly charged, deeply personal, and rife with emotions for many in the room. As a heterosexual cisgender fundraiser without lived experience, it was a privilege to be able to attend and engage. I’m very grateful my fellow attendees welcomed my presence as an ally.

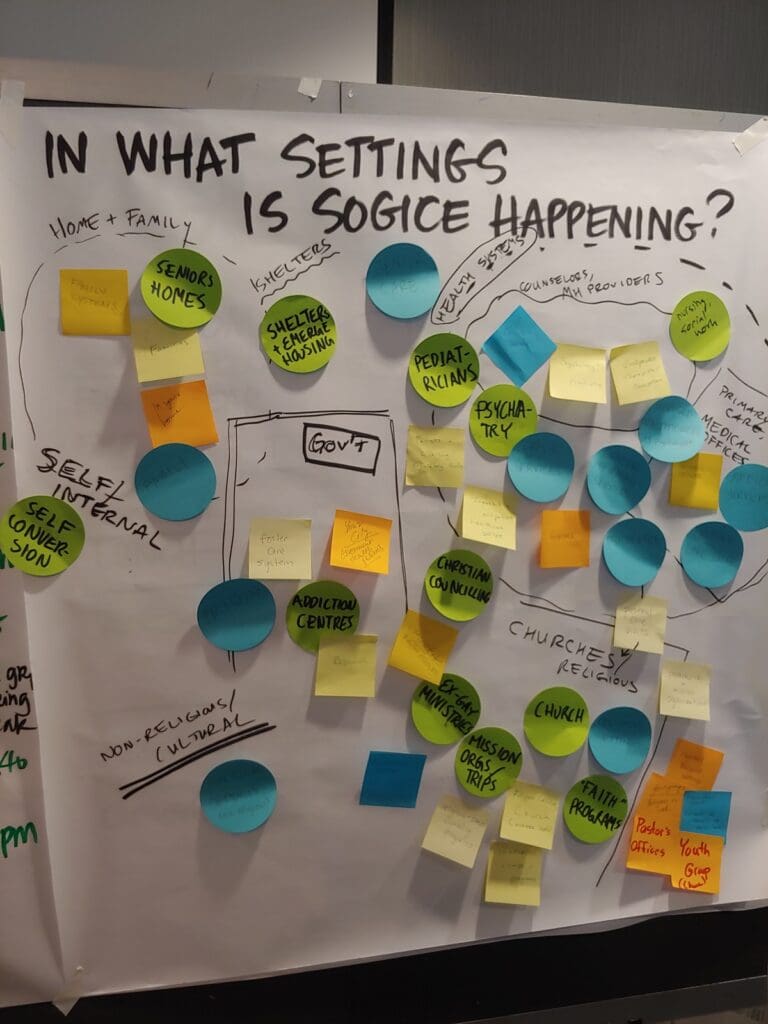

A quick definition to explain what I’m talking about: we use the term “conversion therapy” to describe sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts (SOGICE). That’s a mouthful, but it’s exactly what it describes: trying to change, convert, or “repair” one’s sexual identity to heterosexuality, or trying to change one’s gender identity to cisgender. “Conversion therapy” is far from a perfect descriptor, but it seems to be the most familiar terminology.

I was invited to attend on behalf of the BCCDC Foundation because of our role in supporting the work that was to take place in the room that day and subsequent work to come. At the Foundation, it’s our job to understand the issue or project for which we’re fundraising in order to galvanize support around it. Being able to attend this dialogue event was the chance to see our donors’ generosity in action and use what I learned there to advance the work.

I’m embarrassed to admit that prior to speaking with Dr Travis Salway (social epidemiologist and researcher at the BCCDC who is leading this work) in September, I had no idea that conversion therapy was still being practiced in Canada. Sure, I had heard of it before, but I thought there was no way this was still happening in 2019. Not a chance, I thought. I also thought that these were practices that happened solely in religious contexts. No way would a licensed medical practitioner impose this on patients seeking support.

On both accounts I was very, very wrong.

I have since learned that conversion therapy is happening right now in Canada. There are known groups and institutions operating across the country, and many more individuals unknown to us. And there is a history of health practitioners–doctors, social workers, counsellors, and therapists under the public healthcare system and privately–who have perpetuated these practices. Nearly everything I thought I knew about conversion therapy was wrong.

The purpose of the event was to develop the ideas that would catalyze novel research on the health needs of survivors and identify policy and legislative paths to end conversion therapy in North America.

There were 32 of us in attendance, and half of us had personal experience of conversion therapy. Everybody’s story, perspective, and role was different, but as a few folks in our group pointed out: despite our differences, we all had a shared commonality between us. We all know that survivors need to be heard, that conversion therapy causes deep harm, and we have to end it.

In preparing for the event, I did my research. I read testimonials and articles by survivors who described what they went through as torture; I watched films about the damage it causes; and I reviewed statistics like an estimated 20,000 LGBTQ2+ Canadians have been exposed to conversion therapy and how one third of survivors have attempted suicide. I understood the issue, the impacts it has, and why this is an important health and policy issue that we need to address. But I didn’t really grasp what that meant on a human level until I sat across from the folks who had lived it.

A lot of our work was focused and goal oriented–discussing what supports survivors need, what institutional change can look like, policy and legislative action options, and how do we communicate about this to the public to raise awareness and garner support. Interspersed with this, folks shared what they experienced and their challenges coming out of conversion therapy. Their stories ranged, but they were consistently heart-wrenching. I struggled to control the lump in my throat more than once, listening to the vulnerability of these perfect strangers sharing some of their greatest pains.

What I took away from their stories is that their trauma is not something that is experienced in a singular moment, or on a particular day. It’s not like a car crash; there isn’t a moment of impact where injury is sustained, followed by stillness, and then care and attention can be administered for healing to begin.

With this kind of trauma, the stillness doesn’t necessarily come. The injury continues, ongoing, often for years. One is left in a sustained moment-of-impact, where care and healing is attempted, but how can we heal if we’re being continuously re-injured?

What I witnessed was a group of incredibly brave people, of different backgrounds and identities, trying to still–years later–find their way through that injury to heal.

For those who have survived, the damages to identity, self-worth, and mental well-being linger. And then there’s some who haven’t.

This isn’t to characterize all as victims. Despite the immense pain they’ve endured, there was also amazing resilience in the room. Finding the strength to be there and share their stories takes real bravery and power. And that bravery and commitment to galvanize change for the better was what was truly inspiring. It’s because of that, that I know the changes and support we’re seeking are possible.

But what does this have to do with public health, and why we as a public health charity were there? Stay tuned for part 2 of my reflections where I’ll dig deeper into the “bigger picture” takeaways from this event. If you want to spur change now, join the movement, and make sure thousands of survivors can access the justice and support they need. You can make a gift to support this work, subscribe to our monthly newsletter, and engage with us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram where we’re talking a lot about this issue.