Guest post by Dr Sarah Henderson

Senior Scientist, Environmental Health Services, BC Centre for Disease Control

Associate Professor (Partner), School of Population and Public Health, UBC

They say that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert, which makes me an expert at worrying about wildfire smoke.

Since the 2003 firestorm in British Columbia, I have been grappling with this unpredictable and extreme form of air pollution that periodically affects very large populations. I have worried even more since the unprecedented wildfire seasons of 2017 and 2018, because climate change is increasing wildfire risk all over the world. Australia is my second home, and I have watched the devastating wildfires and smoke with a heavy heart – especially because I know that something similar could happen in BC, or elsewhere in Canada.

We already understand a lot about the health effects of air pollution from sources such as traffic and industry, and we’re learning more all of the time. For example, people who live in more polluted areas have shorter life expectancies due to higher risk of many chronic conditions including heart disease, respiratory disease, diabetes, dementia, lung cancer…the growing list seems endless. On days with more pollution more people will visit their doctors, go to the emergency room, be admitted to the hospital, and some will die prematurely. Babies who are exposed to more pollution while in the womb face more health challenges than babies who are less exposed. Simply put, there is overwhelming evidence that air pollution is unhealthy for humans at all stages of life.

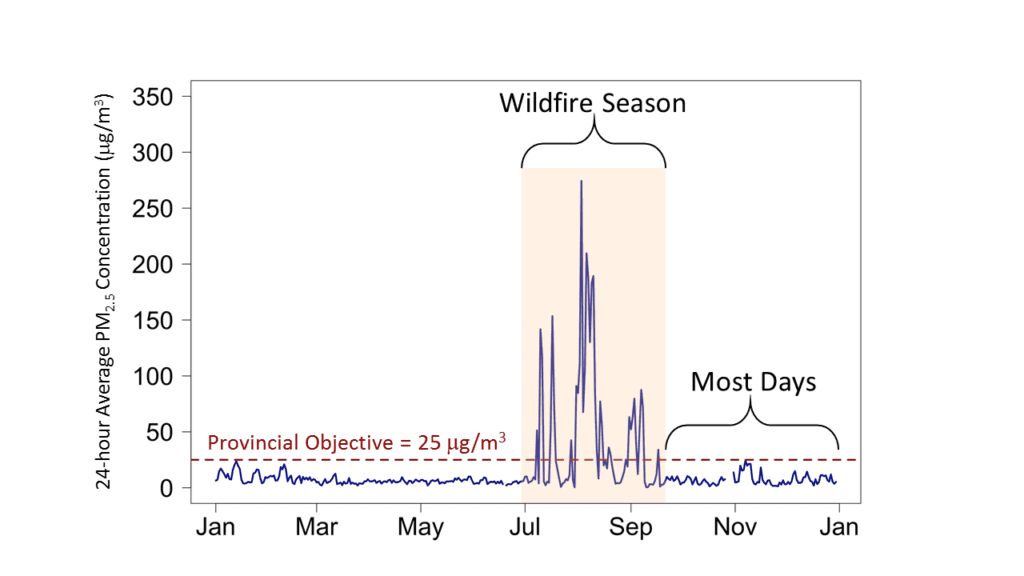

Air pollution sources such as traffic and industry emit predictable amounts of pollution every day, day after day, year after year. Air pollution from wildfire smoke is really different with respect to its timing and intensity. Big wildfires, on the other hand, only happen in the summer, they don’t happen every summer, and they emit a lot of pollution when they do happen. During wildfire season, air quality can be more than 20 times worse than we would expect on typical days (Figure 1). Because of these differences, we don’t yet completely understand the health effects of wildfire smoke.

For the past few years I have worried about unborn and newborn babies who are exposed to wildfire smoke. I worry about babies in the womb because wildfire smoke can cause systemic inflammation during pregnancy, which may affect the flow of nutrition through the placenta. We know from one large study in California that pregnancy during an extreme wildfire season was associated with slightly smaller babies than expected and we know from other studies that low birth weight can be associated with poorer lifelong health. I worry about newborn babies because they have incredibly sensitive lungs, and exposure to wildfire smoke may do damage that never fully heals. We know from another study in California that a group of newborn monkeys exposed to wildfire smoke had smaller lungs and poorer immune function in adolescence than a similar, unexposed group.

We need more research on babies exposed to wildfire smoke because the detrimental effects may last a lifetime. With the support of the BCCDC Foundation, my team was recently awarded a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to study how the extreme 2017 and 2018 wildfire seasons affected babies in BC. The BCCDC and Perinatal Services BC will collaborate to study the effects of wildfire smoke on pre-term births, birth weight, and healthcare usage during the first years of life.

In a couple of years, these results will help to protect unborn and newborn babies during wildfire seasons in BC, California, Australia, and anywhere else that experiences episodes of extreme smoke. Until then, I encourage everyone to worry a little bit about wildfire smoke – you don’t have to become an expert, but taking precautions to limit your exposure will help to protect your health.