Guest post by:

Sofia Bartlett PhD

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Clinical Prevention Services at the BC Centre for Disease Control & Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, UBC

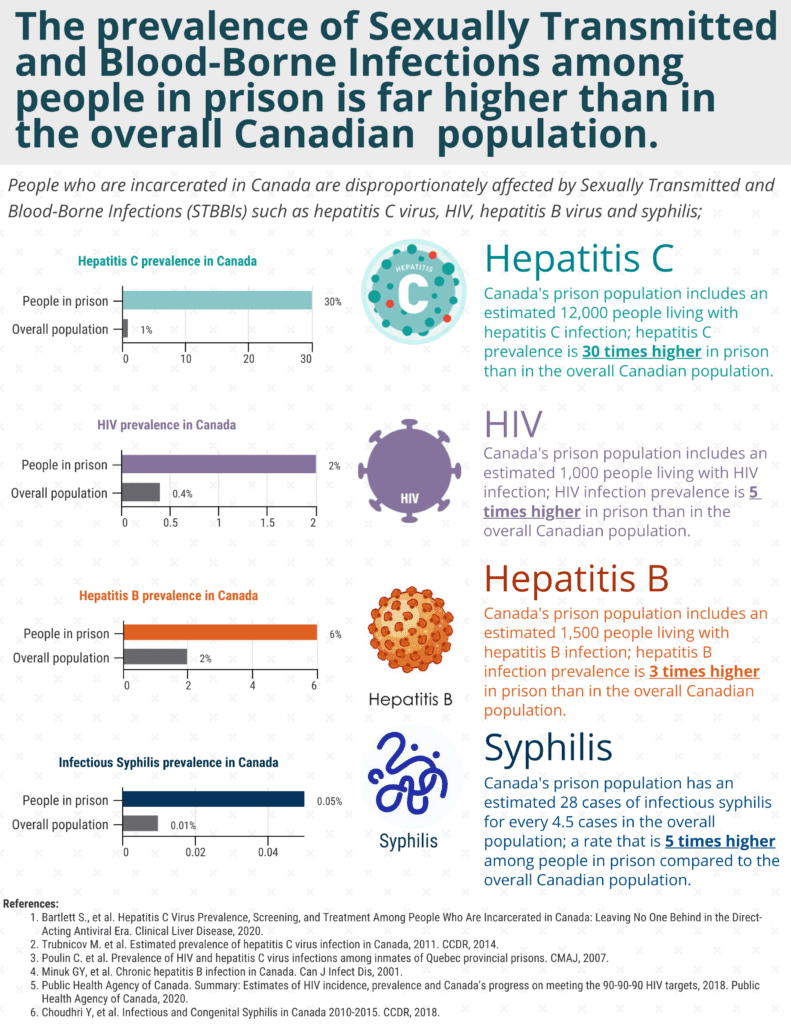

Among people who are incarcerated in Canada, there are an estimated 12,000 people living with hepatitis C infection at any one time, which is a rate of infection almost 30 times higher than in the overall Canadian population.

The disproportionate burden of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (STBBIs) among people who are incarcerated isn’t limited to hepatitis C though; the rate of HIV infection is 5 times higher, the rate of hepatitis B infection is 3 times higher, and the rate of infectious syphilis is 5 times higher among people in prison, compared to the overall Canadian population.

These infections can lead to serious health complications; for people who are pregnant, infectious syphilis can be passed on to their infant, which leads to lifelong health issues and can also result in infant death. Syphilis is the third most commonly reported STI in Canada now (behind Chlamydia and Gonorrhea), and neonatal syphilis cases in Canada have surged in recent years.

Chronic hepatitis C infection is the leading cause of liver disease in Canada, which is ranked 11th in 2019 among causes of death. While hepatitis B is a vaccine preventable disease, many people living in Canada were born in countries where this virus is highly prevalent and vaccination is less common, resulting in an estimated 250,000-460,000 Canadians living with chronic hepatitis B infection.

There is good news though; there are sensitive tests available to detect all these infections, and effective treatments are available. Hepatitis C and syphilis are curable, while HIV and hepatitis B infection can be suppressed, preventing the viruses from replicating or being able to be passed on.

Despite this, people who have experienced incarceration continue to face many difficulties in accessing testing and treatment for STBBIs, both while they are in prison and when they return to the community. There is a lack of trust and power imbalances between people in prison and the health care staff, and these further exacerbate issues related to STBBIs in regards to confidentiality and stigma. Knowledge gaps related to STBBIs, among both people in prison and the staff have also been reported. When coupled with staff shortages and other resource limitations, these issues result in gaps in care and missed opportunities to engage people in prison in testing or treatment for STBBIs.

While we continue to have a large group of people who are disproportionately impacted by STBBIs and yet unable to access care, such as people who have experienced incarceration, we are not be able to adequately address these infections in our communities. For this reason, addressing these barriers to STBBI care in prisons is a high priority.

To do this, we need a new paradigm in prison health care, and with funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada, this is what the BC Centre for Disease Control and BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services hopes to achieve through the ‘Pathways to STBBI Care in BC Provincial Corrections Project’.

As part of this project, we have been conducting educational workshops on STBBIs with staff and residents in BC Provincial Correctional Centres, as well as people with lived experience of incarceration (PWLE) in the community, then doing surveys to get input from them about their previous experiences, preferences, and needs related STBBI testing and care.

This information is being used by a Committee, which includes people with lived experience of incarceration, as well as researchers and health care providers, to create a new policy and guideline on STBBI testing and care for BC Provincial Corrections. Staff and residents, as well as PWLE of incarceration in the community, will also get the opportunity to review and give feedback or suggest changes to the policy and guideline before it is implemented.

Through centering PWLE of incarceration in the development of policies and guidelines related to STBBI testing, we hope to help them become an active partner in their own health care, giving the new policies and guidelines the greatest chance of improving STBBI outcomes for people in prison in BC.

BC Centre for Disease Control is also working on other transformative projects to improve health outcomes for people in prison related to STBBIs; we recently received funding for the Test, Link, Call (TLC) Project which will begin shortly. The TLC Project will provide smart phones with 6 months of calling credit to people living with hepatitis C infection at the time of release from provincial corrections, along with a transitional care plan for hepatitis C treatment.

The care plan and cell phone will help them connect with peer and social supports, as well as a treatment provider of their choice in the community, and phones provided will also be preloaded with the LifeGuard app, to further assist in meeting the unmet health needs of people leaving prison.

Interested in reading Dr Bartlett’s guest post “Uncovering SARS-CoV-2 Behind Bars: Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Correctional Settings”? Go here to read her article.