An interview with the Principal Investigators for a BCCDC study assessing the equity of misinformation and communication on COVID-19 in BC:

Guest post by:*

Katie Fenn

Director, Quality, Safety & Accreditation, Safety & Accreditation

Harlan Pruden

Educator, Chee Mamuk, CPS Chee Mamuk

Emily Rempel

Knowledge Translation Lead, Overdose Surveillance and Antibiotic Stewardship

Can you tell us what an infodemic is? Is it the same thing as misinformation?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) an ‘infodemic,’ is a flood of health information. Some of it wrong, some of it right. Misinformation is the spread of wrong or misleading information. Disinformation happens when the information shared is a deliberate attempt to undermine the public health response and advance alternative agendas of groups or individuals.

What inspired you to take on a research project related to misinformation?

Misinformation has the potential to harm peoples’ physical and mental health. When people are faced with so much information, it can be hard to sift through what’s right and wrong. This can lead to people doing the opposite of what public health recommends. More worrying, it can lead to things like stigma and, as we’ve seen in the COVID-19 pandemic, racism.

What did your research project look at?

Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, our team wanted to understand the level of misinformation locally. We wanted to understand different communities’ communication needs to ensure we were meeting people where they are at. Through an online survey, we asked British Columbians where they look for trusted COVID-19 information. We also asked about their demographics; COVID-19 knowledge; healthy and harmful coping behaviours; and stigma and discrimination.

Can you share some background on your study?

Our research project consisted of a survey of 3,073 British Columbians. We collected data from April 14th to 19th, 2020. The survey was only in English, but we purposefully wanted to understand the experiences of our non-White populations so we included Chinese, Indigenous (e.g. First Nations, Métis, Inuit, etc.), South Asian (e.g. East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, etc.), and Southeast Asian (e.g., Filipino, Vietnamese, Thai, etc.) British Columbians.

What did you find in your survey?

This is where it gets more interesting! Let’s take up conversation by focusing on a few highlights.

Misinformation: Despite the fact that there was, and is, no known treatment for COVID-19, about half of our survey respondents believed in various forms of treatment. The overall confusion was high, and people deferred to treatment options they may traditionally apply in other cold or flu like scenarios. Of particular concern was the 1 in 5 people who believed that antibiotics are a COVID-19 treatment. We know that antibiotics only treat bacterial infections and could never treat COVID-19.

At the time of the survey, there was much information circulating and being reinforced by influencers like Donald Trump (not our president!) on the use of hydroxychloroquine. Around 1 in 3 respondents also believed this to work; illustrating the harm those with a high degree of media and social media presence have with misinformation/disinformation.

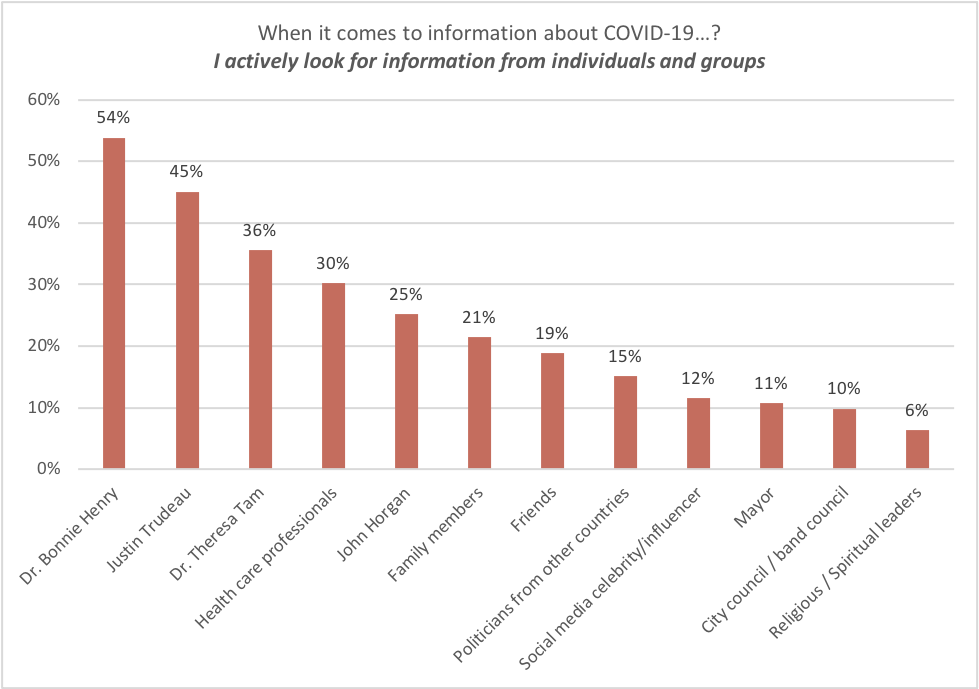

Communication Preferences: It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Dr. Bonnie Henry is where the majority (54%) of respondents actively looked for COVID-19 information. At the same time, the reverse should be noted that 46% were notlooking to Dr. Bonnie Henry. As she is our primary communicator for COVID-19, this shows the need to amplify and diversify our communication strategies.

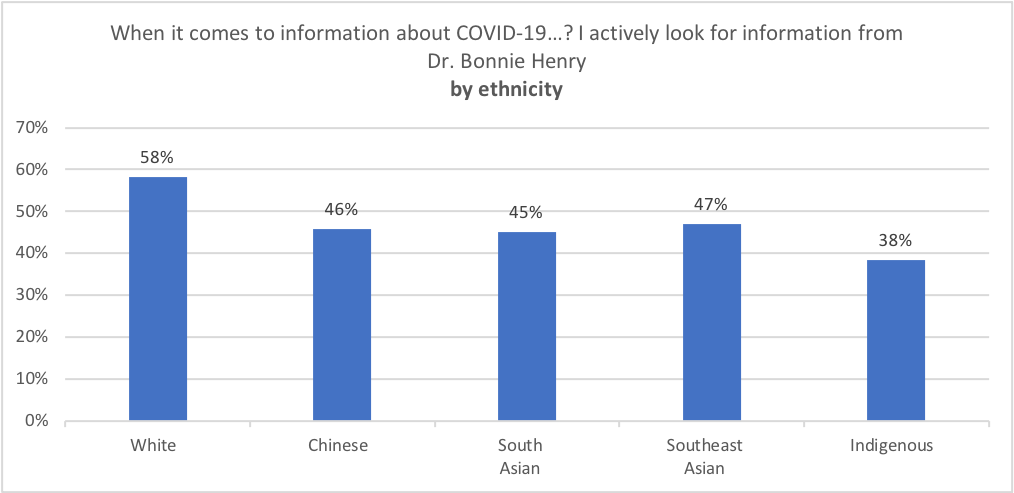

To understand who is not looking to Dr. Bonnie Henry, we broke our analysis down by age and ethnicity. We can see a clear opportunity to work to increase Dr. Henry’s reach into South Asian and Indigenous communities.

However, we also know it’s more important to meet people where they already look for information. Select examples include the greater use of Facebook amongst Indigenous respondents and the use of YouTube and WhatsApp by South Asian respondents. Younger respondents, as expected, were much less likely to seek information from TV news and much more likely to look to social media like Instagram.

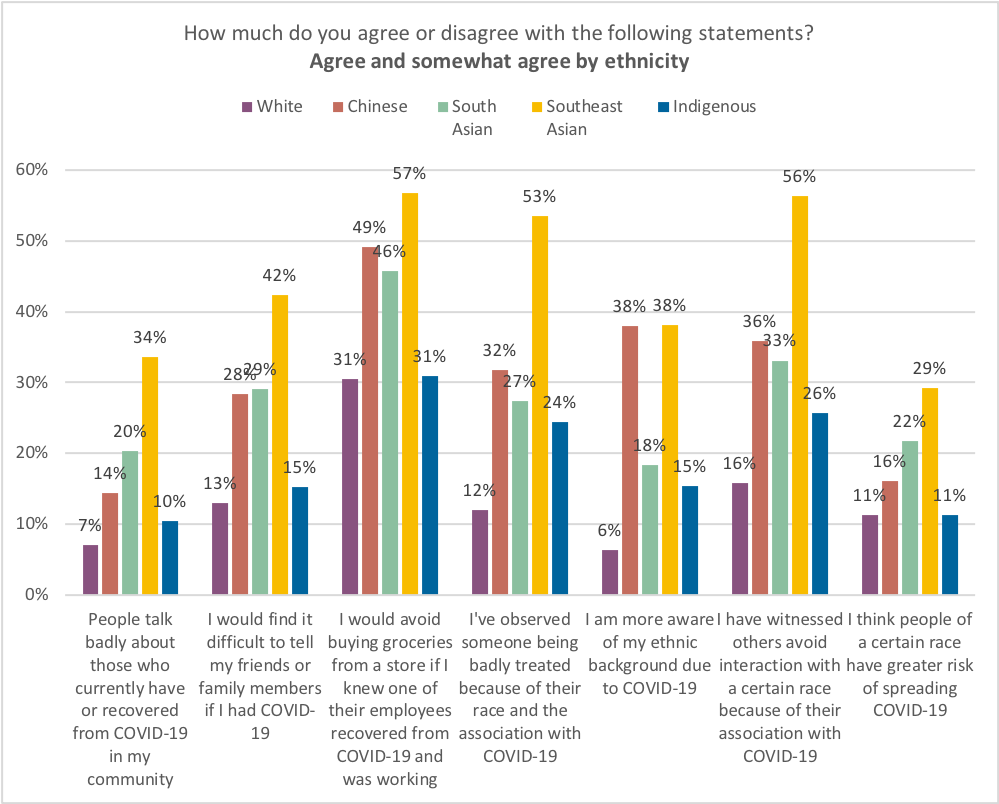

Stigma: 38% of Chinese respondents reported being more aware of their ethnic background due to COVID-19. 1 in 3 Chinese British Columbians also observed someone being badly treated because of their race and association with COVID-19. This is also true for 1 in 4 Indigenous and South Asian respondents. While only 1 in 10 White respondents report the same.

So what does this all mean and what are the next steps?

We found that non-white ethnic groups in BC are experiencing the COVID-19 crisis differently than white publics. Not only do non-white publics tend to seek information from different sources, but they also experience stigma at a much higher intensity. Since April we have been working with external and internal partners to find solutions to our communications gaps, and to help improve the public health response to COVID-19. Some examples include the development of the BCCDC COVID-19 Language Guide and personas of social media users to guide messaging. We are also planning to re-run the survey to see what’s changed over time.

Interested how you can help combat misinformation everyday? Click through to Addressing the Infodemic: Everyone Must Play a Role in Stopping Mis- and Disinformation.

*Bios:

Katie Fenn has supported numerous quality improvement initiatives within public health including the patient to population project, making space for health equity, improving data quality, and point of care testing for HCV. Her interests are in process improvement and strategic planning through partnerships and communication. She has worked across many sectors including the Commonwealth Games, Advertising, Community Living, and Event Planning.

Dr. Emily Rempel is a mixed white and Métis public engagement and social sciences researcher. She has a PhD in policy and public engagement from the University of Bath in the UK. Her current role is a Knowledge Translation Lead at the BC Centre for Disease Control. Her work focuses on equity in public engagement and knowledge exchange in the fields of public health, critical data studies and biostatistics.

Harlan Pruden (nēhiyo/First Nations Cree Nation), works with and for the Two-Spirit community locally, nationally and internationally. Currently, Harlan is an Educator at Chee Mamuk, an Indigenous public health program at BC Centre for Disease Control; the Managing Editor of the TwoSpiritJournal.com; and an Advisory Board Member for CIHR’s Institute of Gender and Health, whose mission is to foster research excellence regarding the influence of sex and gender on health and to apply these findings to identify and address pressing health challenges facing men, women, girls, boys and gender-diverse people including Two-Spirit people.