Guest post by Megan Oakey, MPH, B.HK

Provincial Manager for Injury Prevention, BC Centre for Disease Control

In my area of public health expertise, injury prevention is an issue that often struggles to receive attention. I don’t say this to complain. Quite the contrary. The prevention of injuries tends to suffer from some very interesting human bias. But I will get to that later.

First, how do we define injury and what is the problem?

As you likely know, an injury is physical damage to the body as a result of excessive force, heat, chemicals, or sometimes the absence of chemicals, like oxygen.

In my field, I’m concerned about serious injuries that kill or significantly harm people. Minor injuries like scrapes or bruises, though unpleasant, are ones we can heal and learn from.

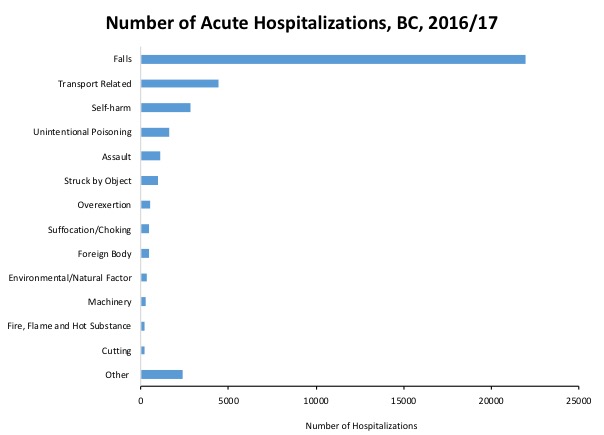

Serious or fatal injuries could be from a fall, car crash or gunshot wound, an opioid overdose or childhood poisoning, drowning or suicide by hanging, burns, and so on. When you start to see all the causes listed out, it’s pretty grim.

Each year, over 35,000 British Columbians visit the hospital for an injury, over 8,000 are left with a permanent disability as a result of an injury, and over 2,400 die. This is the equivalent of 5 jetliners crashing with all lives lost, each year. Or, the equivalent of 1 person dying from an injury every 4 hours.

Injuries are the number one reason someone between the ages of 1-44 dies. You are 5 times more likely to die of an injury than you are of cancer during that period of your life. These deaths are not just statistics—they leave gaping holes in families, communities, schools, and workplaces.

So why do these things still happen?

All of these different ways we can be hurt also appear disparate from each other–my grandmother’s broken hip from a fall seems completely unrelated to an injury from a car crash. When you add them all up, our brains for some reason do not see the sum to be as great as their parts.

In addition to thinking the problem is smaller than it really is, research reveals another interesting bias: that most of us think that serious injuries are inevitable—simply a part of life. However, we often tell ourselves that serious injuries don’t happen to us, they only happen to other people. Plus, we accept risk in some aspect of our lives (driving a car) but not in others (jumping off a cliff).

When was the last time you called an injury an “accident”? Was it really inevitable, or could something have been done to prevent it? In reality, most serious injuries are preventable.

What works?

Reminders at the moment of highest risk are effective. Education is important too, but it tends to be the least effective way to stop injuries from occurring.

Because of our biases and life around us we will always make mistakes. So most of my work, and that of my colleagues, focuses on interventions that take human fallibility out of the equation. Policy change and engineering are the ‘big wins’ of injury prevention because the amount of lives that can be saved is huge. A median barrier down a highway that stops fatal head-on collisions is infinitely better than imploring the public to drive the speed limit (90% of head-on collisions are fatal at 90km/hr).

In public health, we work with health care, government ministries, and policy makers to pass laws and regulations that are grounded in evidence. For instance, did you know that most pedestrians are killed during the winter months, at night, in the rain, when both the pedestrian is crossing legally and the car is legally turning left or right? Would high visibility clothing work? The evidence says no. Thankfully, the effective solution is simple. The light should not be green when the pedestrian walk signal is on, thus separating the road users in time and space.

What can you do to prevent injuries?

First, stop referring to injuries as “accidents.” Try using words like “incident” or “crash.” Changing how you speak about injuries can start to make you see them as preventable.

Second, learn about effective policy and engineering interventions; there are so many: childproof second story windows, four-sided pool fencing, lower speed limits, separated cycle lanes, larger steps on staircases. Not every cause of injury will have solutions like these, sometimes education is indeed necessary. But wherever you can, look to the system that surrounds us.

And then help advocate with your local government for sidewalk fixes so seniors do not experience a fall, write a letter to your MLA that you want 30km/hr speed limits on local streets, and support groups who advocate for suicide barriers on bridges.

Use your voice to support effective solutions that can make all the difference to thousands of British Columbians.

Megan Oakey is also co-chair of the BC Provincial Public Health Injury Prevention Committee, co-chair of the BC Injury Prevention Alliance, and chair of the BC Falls and Injury Prevention Coalition. The BCCDC Foundation has previously funded Megan’s work through our Open Awards Program.

Activate Health is a battle cry to be a health ambassador in your community. By using your voice and taking action you can improve health for British Columbians. Join us in Activating Health today.