Reflections from the past year of public health research

Guest post by Dr Travis Salway

Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, SFU

Working in affiliation with: The BC Centre for Disease Control, The Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity, and the Community-Based Research Centre

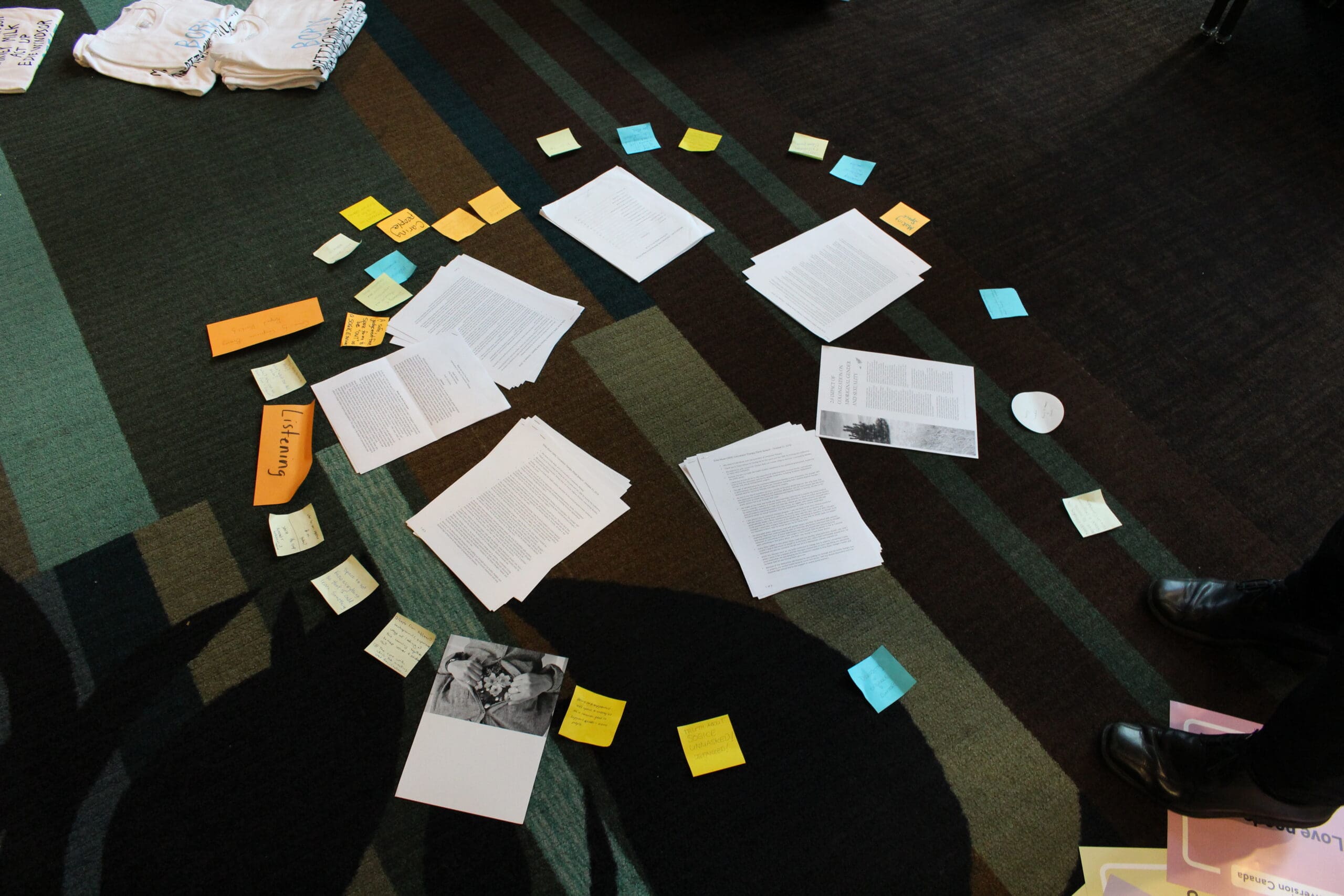

In the fall of 2019, the BCCDC Foundation launched a campaign to give voice to the many Canadians who have endured so-called “conversion therapy.” Funds were used to support a unique and powerful Dialogue event where we heard from survivors and LGBTQ2 community leaders about research priorities for preventing future and ongoing trauma related to conversion therapy.

In this post, I reflect on what we have learned from the past year of active research, as well as advocacy efforts with the federal government, who first expressed interest in banning conversion therapy the month following our campaign and Dialogue event, when Prime Minister Trudeau mandated that his Ministers prepare a Criminal Code amendment that would prohibit conversion therapy across Canada.

Q. What have we learned about conversion therapy from Canadian research conducted in the past year?

In the spring of 2019, I was invited to give a statement to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health about what further action the federal government could take to improve the lives of LGBTQ2 people, acknowledging that we continue to face disproportionately high rates of suicide, depression, and anxiety. When I commented on the need to tackle conversion therapy, MPs asked pointed and sensible questions:

Where is it happening?

Under what circumstances?

How many people are affected?

These questions launched a program of research that continues to this day. Working with the Community-Based Research Centre, we added questions to the national SexNow survey which includes data from over 9,000 gay, bisexual, Two-Spirit, and trans men from across the country—to estimate the prevalence of conversion therapy exposure.

We learned that 1 in 10, corresponding to tens of thousands of Canadians, have had direct experience with conversion therapy at some point in their lives. Many of these experiences were hidden from others, owing to the stigma of attending conversion therapy. In order to break through this silence, we conducted confidential in-depth interviews with 22 individuals of diverse genders and gender identities, asking them to give us more details about the circumstances of their experiences, as well as their suggestions for what more could be done to help them heal from trauma.

We learned that experiences of conversion therapy are varied and complex, but they shared a unifying feature of trying to reject LGBTQ2 outcomes—meaning the adoption of gender identities that differ from sex assigned at birth (for trans people) and/or the adoption of sexual orientations that differ from heteronormative expectations of opposite-sex marriage, etc. (for queer people).

Importantly, we also learned that despite numerous regulatory bodies (including, for example, the Canadian Psychological Association) discrediting conversion therapy, these practices continue to occur in licensed healthcare provider offices, as well as unlicensed settings, including religious organizations. Many attended services that were offered free of cost, while others paid handsomely to experience conversion therapy.

Finally, we learned that many people started conversion therapy as an adult, suggesting that efforts to ban conversion therapy for youth will not sufficiently remove the threat of harm for LGBTQ2 people.

Q. How can federal legislation stop conversion therapy from continuing to happen?

In this context, there was great enthusiasm for the federal bill (now labeled C-6), an Amendment to the Criminal Code to ban conversion therapy. Several researchers, survivors, and activists—myself included—gave testimony to the Justice Committee in December of 2020, urging legislators to expand the scope of the bill. My team made the following recommendations based on the research above:

- Improve the definition of conversion therapy to clarify that the defining feature is not “changing” intrinsic sexual orientations or gender identities, but rather indoctrinating attendees with the notion that certain (i.e., LGBTQ2) orientations, identities, and expressions are disordered, less desirable, or otherwise modifiable.

- Include specific language to address conversion therapy practices that target trans people. Here we drew examples from our interviews but also pointed to an open letter led by trans conversion therapy survivor and activist Erika Muse, signed by hundreds of individuals and organizations from across Canada.

- Include a provision to ban promotion of conversion therapy that may not include financial or material benefit (i.e., free services).

- Expand the ban to include adults.

- Advocate for the provision of federally funded supports for conversion therapy survivors, including trauma-informed and survivor-directed healing efforts (counseling, peer groups, etc.).

The Committee made some of these recommendations, though not all, and the bill is currently awaiting third reading on the floor of the House. Those of us working on this issue believe that it is important to continue pushing legislators and policymakers, federally and provincially, to clearly communicate to Canadians of all ages that LGBTQ2 identities are celebrated, and that conversion therapy practices are incompatible with Canadian values.

There is no silver bullet to stopping conversion therapy, and we therefore continue to insist that effective and holistic strategies will include, not only bans and similar deterrents, but also comprehensive, affirming education and support provided to LGBTQ2 people to clearly communicate alternatives to attending conversion therapy.

Q. What else can we do?

Many of the individuals we interviewed experienced intense and distressing messages of rejection before they even arrived at conversion therapy. I have previously referred to this layering of anti-LGBTQ2 messaging as the “conversion therapy pyramid.” It suggests that we have an opportunity to prevent the demand for conversion therapy by fervently and consistently delivering LGBTQ2-affirming messages to Canadians, starting with schools and other settings that serve our youth.

For example, Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights has been advocating for federal and provincial consistency in guidelines that promote LGBTQ2 well-being within school-based sex ed. This initiative can have enormous ‘upstream‘ impact on LGBTQ2 populations, by reducing what researchers call “minority stress” thereby redressing some of the enormous inequities we continue to experience when it comes to mental health outcomes, including suicide.

Most importantly, all of us, LGBTQ2 or otherwise, need to listen carefully to the experiences of those who have endured conversion therapy. If you are like me, your first instinct may be to avoid the topic or even deny that such practices exist in our contemporary notion of a ‘progressive’ Canada. This is a disservice to those who have experienced these traumas.

Below, I have included some links to where you can start to read and listen to survivor stories. My hope is that the experience of story-telling will be meaningful and even healing for the survivors and that sharing these stories will lead more Canadians to reflect on how these practices have continued to operate, unchecked, for so long.

- Our research team’s brief to the federal Justice Committee (December 2020)

- Community-Based Research Centre

- Centre for Gender and Sexual Health Equity & open letter from survivor and activist Erika Muse

- No Conversion Canada

- Federal Bill C-6

- My reflections on previous legislative attempts

Acknowledgments:

This work was made possible due to the ground-breaking advocacy efforts of Canadian conversion therapy survivors. The research was supported by the BCCDC Foundation, the Community-Based Research Centre, Andrew Beckerman, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.